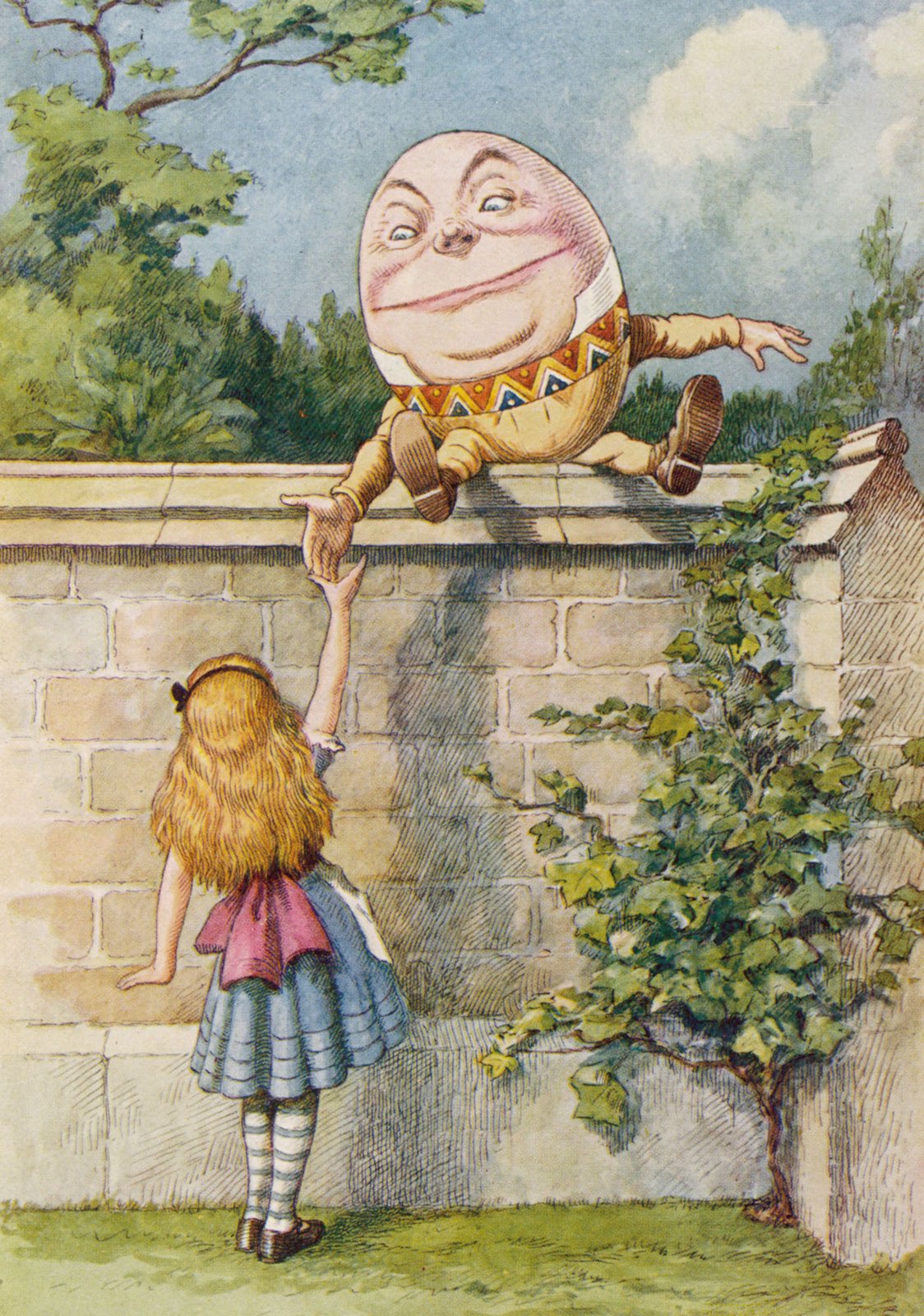

“When I use a word,” Humpty Dumpty said, in rather a scornful tone, “it means just what I choose it to mean — neither more nor less.”

“The question is,” said Alice, “whether you can make words mean so many different things.”

“The question is,” said Humpty Dumpty, “which is to be master — that’s all.”

Both Alice and Humpty Dumpty have a strong case. Alice is justified in her complaint that words can and indeed often do mean many different things and that this can be most confusing — and can be injurious. More confusing to some than others. There are those who simply cannot cope with confusion. Psychologists have referred to this as the fear of ambiguity. Like other fears it terrifies and often paralyzes people.

Both Alice and Humpty Dumpty have a strong case. Alice is justified in her complaint that words can and indeed often do mean many different things and that this can be most confusing — and can be injurious. More confusing to some than others. There are those who simply cannot cope with confusion. Psychologists have referred to this as the fear of ambiguity. Like other fears it terrifies and often paralyzes people.

Consequently there are those who try to use words and sentences in a way which reduces ambiguity for no other reason that they wish to be clearly understood by others and that they want to understand what others are saying,i.e. interpreting messages correctly. Often such messages are trivial, but what if in fact such messages are of utmost importance? As in, “Call 911! Your house is on fire!”

Humpty Dumpty’s proposal that words are assigned a restricted meaning by fiat — “it means what I wish it to mean” — would result in an the construction of an endless dictionary. Everyone would then have the right — even obligation — to usurp the meaning of a word which already exists and entered into their idiosyncratic dictionary! We would be forced to live in a world of neologisms and would need also need all the sounds we could produce with our versatile larynx to cover our needs to communicate our thoughts to others! Babylon will have come to pass. Existing languages would be wiped out! An unimaginable event. Just imagine the effect on our dictionaries.

The alternative to this bizarre doomsday scenario would be to deplete our vocabulary as far as possible,to whittle it down to the smallest number of items. Isn’t this familiar? Basic English was once favoured by one of the finest exponents of current English, Winston Churchill. Rewrite Shkespeare even Jane Austen into B.E. and translate Tolstoy also!

But the current trend is actually diametrically opposed: we actually need more and more words to name things and to identify the many new items we have introduced into the world; the many new objects we have discovered or designed and manufactured; to mark novel events which form our personal and public experience and which help us to identify new norms; as well as the multitude of new ideas we have developed.

There are many people, dead and alive, who share my name — but I reckon few who also carry my initials, H.M.B. — and fewer, if any, who also share my birthday and birth year. These are all markers of my identity. So using this method, Humpty Dumpty’s complaint could be taken care of, simply by embellishing existing words, by adding descriptions when appropriate or desirable, or by giving each set of words a contexts.

We do this already: “Yonder horse” is not any old mare, but a particular horse, perhaps the horse standing on the meadows nibbling grass, or kicking its heels. In this case *yonder* is not an object description, but one that identifies the horse by its context, rather than by such unique peculiarities as as the length of its mane.

But I appear to have urged a tedious solution. If either Alice or Humpty Dumpty remain concerned that their use of a word may be misunderstood, they could hang out a warning sign: “This word is in my lexicon — but may not be in yours” — let’s say “ML” for short. It would distinguish this word from “this word is in our dictionary,” or “OD.”

“ML” refers to words which already exist in some language but which are also used in the lexicon which contains all the words I use — and understand — and which adds to each what I mean by the term. “OD” permits words to be used in a variety of ways and even encourages and promotes ambiguity, as is demonstrated by the number of homonyms cited in the average sized dictionary. (Note: they all cite homonyms, a confession that words have multiple meanings, and that they are ambiguous.)

Usually a competent dictionary insists that there context must be considered — something which restricts how the word listed is to be used. It represents a form of learning which can even be demonstrated by the rat and certainly by many birds. Why not then by little bright middle class girls — and even by other Humpty Dumpties, on or off the wall? Each would be perfectly competent to learn how to use a word in different contexts without getting into a state of total confusion or self—centredness.

Some learn this with little training. There are always exceptions even to this rule. By the way — how many Humpty Dumpties are there?

Delightful!