Entities Part 2B: A note on THE FORM OF THINGS: a timeless problem

What allows us to recognize “bare and higher truths”, truths that emerge only after we have logically tested conclusions against specific principles, those we agree would also lay bare falsehoods? Every truth publicly declared also declares its opposite, namely, what is false. It creates a universe of opposites — of truths and falsehoods — which may lead to the conclusion that whatever is NOT true, must be false!

One may call this imperative falsity, that something is held to be untrue/false because its truth-value has been inferred, not empirically demonstrated. Because we lack reliable, tested, or documented means which allow us to decide between what is false and what is true (ultimately) it may force us logically to talk about “possibilities” rather than with “truths”.

This inadvertently creates a new universe, the world of Possibilities. Possibilities, however, are a form of “speculations”, something done by humans, which is quite strong in some individuals although weak — even absent — in most others. An example of a speculative product is the notion, at first timidly suggested by Greeks during the Iron Age (prior to 600 BC) that the world as known to them had a past, a history during which humans interacted with Gods, who were themselves somewhat “human-like” except that they were opined to have greater powers of control over many more features of the world, e.g. the condition of the seas, the calmness or turmoil of the “elements”, the life and death of other creatures including their existence, even the extinction of all living things. Enter an early version of “Science Fiction”!

Thus, the atoms of Democritus, small, unobservable, and presumably indestructible entities invented c. 600 BC, were entirely speculative. Their nature was unknown but were guessed at. Democritus put out ideas, based on speculations of earlier thinkers, including seers and poets, which others of course were free to accept on the basis of its intuitive appeal, as well as any force of arguments advanced in their favour!

Thus, the atoms of Democritus, small, unobservable, and presumably indestructible entities invented c. 600 BC, were entirely speculative. Their nature was unknown but were guessed at. Democritus put out ideas, based on speculations of earlier thinkers, including seers and poets, which others of course were free to accept on the basis of its intuitive appeal, as well as any force of arguments advanced in their favour!

Democritus had very few followers, but his ideas resonated with other teachers and poets, and did not, as far as is known, draw ire from the religious establishment of his time. Thought-control — although rampant and widely practised throughout preliterate societies — was mainly enforced about matters which affected public policy and religious matters. However, efforts to divert discordant ideas and expunge these from the market place required some form of “thought police”.

As the later history of the Jews shows, the formation and acceptance of a thought-police required a shift in the social status of “prophets” from individuals who were accepted as spokespeople of a God — like Moses was — or of Gods — or of being super-natural forces themselves, those who loudly proclaimed themselves to be superior to existing authorities, on the grounds that they were directly in contact with supernatural forces.

From phenomenological, personal insights to possessing public knowledge: the impossible path

The problem which early thinkers addressed was how the complex phenomenological world — the world of daily experience, the world of our encounters which we claim to know — could be construed from visible but also invisible, inherently insensate, events, the things seen and those behind the screen! How do we develop ideas about a world which contains both solids and ephemerals, which could also influence, or “cause”, other events? “The gods at play” are of the latter kind: we guess at their existence on the evidence that things are not as anticipated.

Our anticipations are based on what has happened reliably in the past: however, we need to distinguish *signs* from *omens*. *Signs* presage a future based on earlier experience. *Omens* on the other hand, indicate that the future is likely — or is apt — to depart from the past, that the future is not like the past. So we start from the outset with a view of a corruptible world, where the future is not necessarily like the past.

We do not know what accounts for corruptions. Is there an answer? Early thinkers were bold enough to answer such questions affirmatively: they often were certain that their unique answers were correct! But such guesses were based on insupportable sources of inspiration — and therefore could not survive criticisms. These would fall apart whenever visions of the future fail to materialize which has been all to often — and with great frequency.

Comments on foundational substances

Plato, as successor to Pythagoras, and shortly thereafter Aristotle — thought by many as perhaps the most influential philosopher in Western history and himself a former student of Plato — suggested that regardless of conjectures about foundational substances — the building blocks, like the atoms of Democritus — there were also forms.

Forms serve to give structure to the perceived (subjective) world, a world which necessarily include objects. Some objects were pre-determined, whereas other were “construed”, or seen as themselves products of the elusive mind. But which?

One could argue that structure, the form objects assume, was inherent in these, or one could assume that forms was an attribute assigned to events by the “mind”. Of course, the concept of “becoming assigned” was itself problematic and generated much debate for the next two thousand years. Structure — it seemed to many — was something which was imposed on raw materials, on the analogy that the statue of Athena in Athens was hewn from formless stone. Indeed this analogy is deeply embedded also in the story of the Creation as told by many peoples during the Iron Age, and which was also recorded in their enduring myths.

It seems such myths are part of the history of our own current search for explanations, the search for what is, how things are, and how things become over time: “the past, present, and the indefinite future” as this applies to any event. It appears that during an undetermined earlier moment in our past we transitioned from accepting that some events were indeed time-bound, whereas others others were not. It assumed that some matters were “basic” and “fundamental”, that these events owed their origin to super-human or pre-human agents.

Its history therefore remains beyond our reach — and an explanation for its existence remains on the front-burner of human inquiry, even as I write. We somehow expect that the answers to our root-questions can be gotten. It seems that for the moment, we overlook that any questions raised are themselves culturally determined and that answers to these are therefore “cultural products”, which come and go with time and fashion. (To be sure, there are no fundamental questions — only passing ones and answers: each make their entrances and exits.)

Comments on structure and form

A final word about structure and content: From the point of view outlined so far, the concept of Structure is not self-supporting but is part of a duo: Structure and content are viewed as facets of how we perceive our world. (Note: see also comments in other blogs on “cognize.)

Think of *left* and *right*. But there is also *up* and *down*— and these four concepts define one version of space. The world appears fractionated to us because we employ this perceptual stratagem which permits us to focus on two, four, or more aspects of any experience without regard to raising issue of the origin, or future of the event.

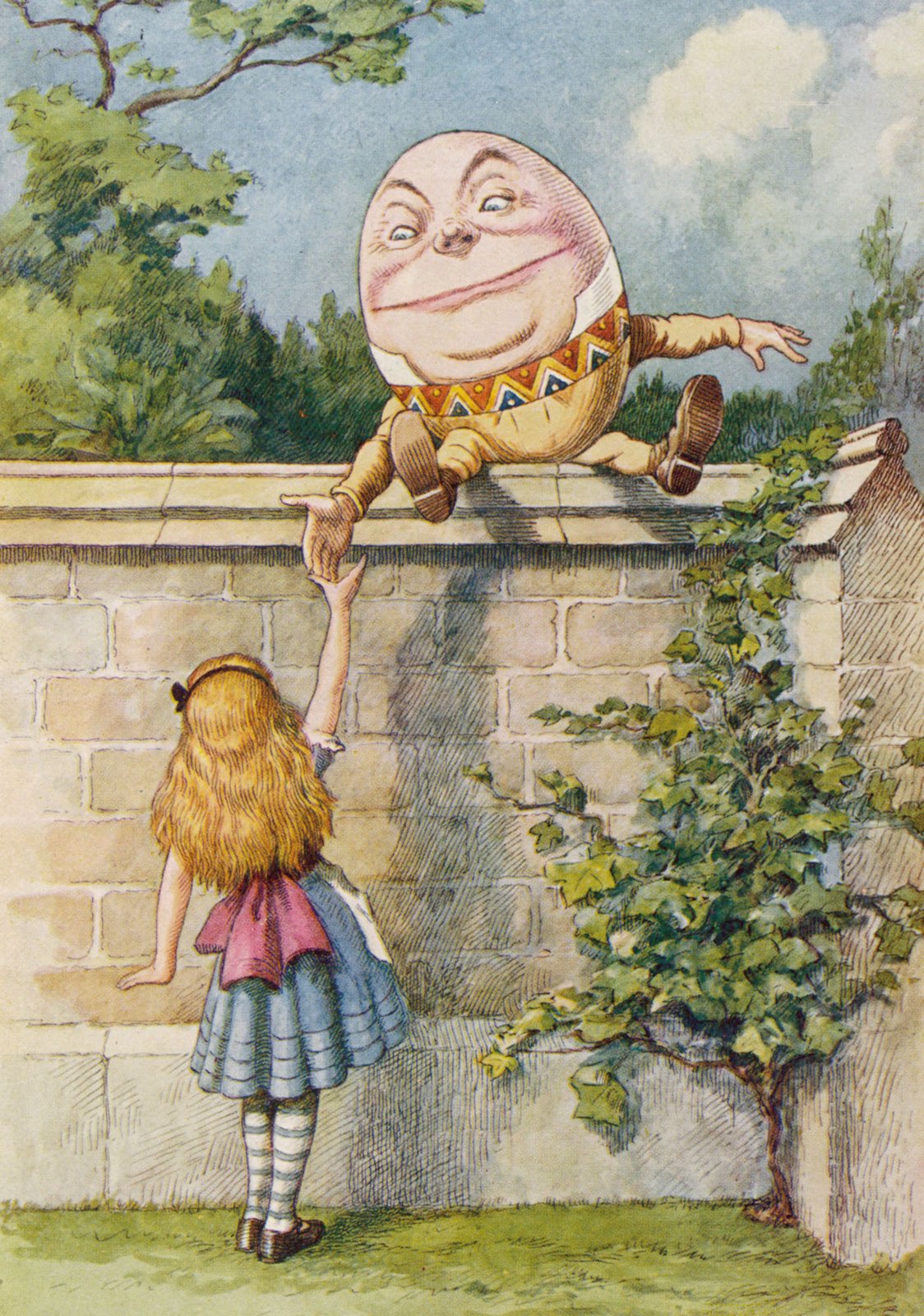

As a result, we invariably create (construct) a world which has self-imposed, limited, dimensions and we therefore deliberately omit two of these — namely, change and passage of time. This creates a contrary-to-fact stance: namely that time stands still, can be tethered but also that the structure of an event can be viewed as timeless, and is close to an “enduring reality”. But is this not a case of the Humpty-Dumpty problem: how to put the pieces together retrospectively, post-hoc, after fall?

One solution may be to accept what had happened and only then back-track, to a pre-event period, before one attempts to reconstruct the world as it was before its fall off the wall and before we construct an alternative end-game, a narrative of its future. In doing so we accept that as observers we have the capacity to write alternative scenarios, no matter at what point the old story was interrupted and diverted.

If form is viewed as that feature of a narrative which gives a story its logical coherence — its rationale — it should be easy to see that any narrative consists of a series of vignettes which could occur in any sequence, or in any order except for the order itself. A story may emerge, but this may happen by chance, like the famed chimps pounding a keyboard and producing the text of Hamlet. Perhaps — but most unlikely.

Structure, it therefore seems, is a property of all things, should be viewed as a universal quality. The world is inconceivable (but only by us) without it, but no more so than a world which is bereft of distinct “instances”. Nevertheless, this world is a convenient fiction whose convenience- value needs to be clearly stated in terms which include the historical moment itself. Thus both Forms and its complementary notion, Substances, are inherently stable but only within limits. That is the conclusion reached here — and it bypasses the religious (pre-empirical) catechism that this is as was ordained! Our conclusion: our perceptions are constrained, but not ordained.

To do so effectively may require that each term is placed in as many contexts as possible. It woud demonstrate to a foreigner unfamiliar with the term, its breadth of use. The foreigner may then search within their home-language for comparable term which is similar in sound and thereupon take the plunge aware that he/she may indeed have guessed incorrectly!

To do so effectively may require that each term is placed in as many contexts as possible. It woud demonstrate to a foreigner unfamiliar with the term, its breadth of use. The foreigner may then search within their home-language for comparable term which is similar in sound and thereupon take the plunge aware that he/she may indeed have guessed incorrectly! It had received support from both Plato and Aristotle although it was clear to them — and to others — that the supposition that the world was constituted in such a manner would have to remain entirely speculative. Methods to test whether indeed such “entitites” as atoms could be discovered — were not available. However there were some who believed that sooner or later suitable instruments would be invented to do so, a hope which helped sustain the wide-spread cosmological view that nature in its physical manifestations could be “revealed”, that the appropriate information would ultimately become available to us.

It had received support from both Plato and Aristotle although it was clear to them — and to others — that the supposition that the world was constituted in such a manner would have to remain entirely speculative. Methods to test whether indeed such “entitites” as atoms could be discovered — were not available. However there were some who believed that sooner or later suitable instruments would be invented to do so, a hope which helped sustain the wide-spread cosmological view that nature in its physical manifestations could be “revealed”, that the appropriate information would ultimately become available to us. Thus, the atoms of Democritus, small, unobservable, and presumably indestructible entities invented c. 600 BC, were entirely speculative. Their nature was unknown but were guessed at. Democritus put out ideas, based on speculations of earlier thinkers, including seers and poets, which others of course were free to accept on the basis of its intuitive appeal, as well as any force of arguments advanced in their favour!

Thus, the atoms of Democritus, small, unobservable, and presumably indestructible entities invented c. 600 BC, were entirely speculative. Their nature was unknown but were guessed at. Democritus put out ideas, based on speculations of earlier thinkers, including seers and poets, which others of course were free to accept on the basis of its intuitive appeal, as well as any force of arguments advanced in their favour! The terms “light” and “dark”, or “hot” and “cold” refer to relative contrasts; whereas “dead” and “alive” refer to opposite and exclusive contrasts of states, or conditions. We also contrast between events by using the adjectival form of a noun, as when we refer to a piece of bread — unquestionably an object — as “stone-hard” or perhaps as “doughy”. In short, nouns are often adapted to serve as adjectives, as qualifiers.

The terms “light” and “dark”, or “hot” and “cold” refer to relative contrasts; whereas “dead” and “alive” refer to opposite and exclusive contrasts of states, or conditions. We also contrast between events by using the adjectival form of a noun, as when we refer to a piece of bread — unquestionably an object — as “stone-hard” or perhaps as “doughy”. In short, nouns are often adapted to serve as adjectives, as qualifiers. I shall therefore compose several pieces in the ELI5 mode. Hopefully adult readers won’t walk away. Please score me 1-10 — the higher the score, the less I have succeeded in stating my case. Give me a 1 if I have succeeded beyond my wildest dreams, and 10 if I have failed miserably, or anything in between.

I shall therefore compose several pieces in the ELI5 mode. Hopefully adult readers won’t walk away. Please score me 1-10 — the higher the score, the less I have succeeded in stating my case. Give me a 1 if I have succeeded beyond my wildest dreams, and 10 if I have failed miserably, or anything in between.

Both Alice and Humpty Dumpty have a strong case. Alice is justified in her complaint that words can and indeed often do mean many different things and that this can be most confusing — and can be injurious. More confusing to some than others. There are those who simply cannot cope with confusion. Psychologists have referred to this as the fear of ambiguity. Like other fears it terrifies and often paralyzes people.

Both Alice and Humpty Dumpty have a strong case. Alice is justified in her complaint that words can and indeed often do mean many different things and that this can be most confusing — and can be injurious. More confusing to some than others. There are those who simply cannot cope with confusion. Psychologists have referred to this as the fear of ambiguity. Like other fears it terrifies and often paralyzes people. In some cases the names were wrought at different times and their names reflect this. A steamer clearly is a boat whose engines are driven by a mechanism whose pistons are moved by steam which is produced by burning coal or oil, whereas a liner is a bigger boat whose propellers or pressure operated valves may be moved by turbines and which carries passengers across oceans, not on rivers and lakes.

In some cases the names were wrought at different times and their names reflect this. A steamer clearly is a boat whose engines are driven by a mechanism whose pistons are moved by steam which is produced by burning coal or oil, whereas a liner is a bigger boat whose propellers or pressure operated valves may be moved by turbines and which carries passengers across oceans, not on rivers and lakes.  Counter-examples: My dog Fifi and my cat Cleopatra are two household pets, each with distinct appearances and ordinary as well as some unusual habits. I can give lots of descriptions of them which will make them familiar, even recognizable to others. I could include a photograph of each and even an odometer-reading! Furthermore their existence is not in doubt, although each has problems articulating their own existence and neither can say “cogito ergo sum” or its equivalent in dog or cat language (of course I would not understand either).

Counter-examples: My dog Fifi and my cat Cleopatra are two household pets, each with distinct appearances and ordinary as well as some unusual habits. I can give lots of descriptions of them which will make them familiar, even recognizable to others. I could include a photograph of each and even an odometer-reading! Furthermore their existence is not in doubt, although each has problems articulating their own existence and neither can say “cogito ergo sum” or its equivalent in dog or cat language (of course I would not understand either).